BÄRO Intara ID

This semi-recessed LED luminaire combines the elegance of a built-in light with the flexibility of a surface-mounted spotlight. Its patented swivel-tilt mechanism allows for a 355-degree rotation and the tilting of the light by 35-degrees. A newly developed LED technology ensures that the light reaches the target surface in a controlled manner and produces soft, defined light cones. Intara ID offers even more flexibility by providing several power ratings, interchangeable optics and a variety of LED spectrums.

Eureka Lighting Prince

Prince is a linear wall lamp featuring a precision-machined glass shade and is enclosed by a chrome frame. The powerful yet highly efficient 17-watt linear LED light is softly diffused through a thin nanostructure micro-lens, while the refractive nature of the glass results in evenly distributed illumination. Supplied with a micro junction box for discreet mounting, it features integrated hooks for easy installation.

IP44 Schmalhorst shot

This outdoor lamp made of diecast aluminium can be freely positioned anywhere on a lawn or in flowerbeds. An accompanying aluminium ring supports the light ball when it is placed on hard grounds, for example patios. Equipped with a flood reflector, shot helps to create focused light effects. Its high-quality workmanship results in a reliable, long service life and makes sure it is easy to maintain.

Zumtobel Nightsight

This series of outdoor luminaires was developed to master the challenges of contemporary urban lighting whilst fulfilling established quality criteria. Nightsight includes a range of different kinds of luminaires, which are designed to illuminate both vertical and horizontal surfaces uniformly, as well as to add specific accents. The calculated use of light and shadow, bright and dark zones, as well as different planes of light serves to set the atmosphere in public spaces.

LED Linear VESTA

Vesta is a linear LED surface mounted luminaire, which was developed for use with base units. To ensure the optimal illumination of work surfaces, the profile allows combinations of fourteen different linear LED lamps and six diffusor optics. The aluminium mounting profile is designed for angles of 30 or 60-degrees, and optionally available in black or silver.

Tobias Grau XT-S Suspension

The XT-S Suspension shows a particularly flat and elegant design of the luminaire head. This is achieved through a combination of advanced LED technology and a newly developed light panel that brings the benefit of providing optimum glare control and light distribution throughout the workplace. The light can be set to six predefined light colours, to a personalised light colour scheme, as well as to the automatic adjustment to the time of day.

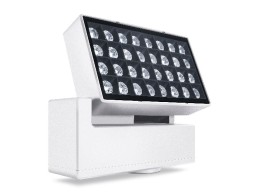

David Morgan Review: EcoSense RISE

When an exterior-rated modular LED projector system with 500,000 options and a delivery lead time of no more than two weeks is launched, then I was keen to take a closer look.

The system is RISE and is the latest offering from US manufacturer EcoSense.

EcoSense is a Los Angeles-based company started in 2009 by the founders of Color Kinetics, George Mueller and Ihor Lys. They met at Carnegie Mellon University while studying for PhDs and went on to build the company into a leading player in the LED lighting market before selling to Philips in 2007. Their patent portfolio includes 50 patents covering a variety of LED technologies including Power Core, the combination of a power supply and control system for LED lighting.

The EcoSense design team has taken a radical approach to the detail design of the RISE projectors, which enables users to change the optics on site while maintaining the IP rating.

At the core of each RISE projector luminaire is a light engine comprising a single Cree high power LED driven by a digital mains voltage driver and fitted with a five-degree custom-designed lens. This light engine can be run at up to eleven watts, is sealed to an IP 68 rating and can deliver up to 700 lumens with more than 40,000 centre beam candelas.

In addition to the single module luminaire, there is a quad version with four light engines in one housing. This luminaire produces 2,800 lumens with over 168,000 centre beam candelas, which is outstanding for such a small form factor.

Unusually, the light engine is a separate module, with the driver mounted behind the LED board that is then fixed into the body casting. Transfer of heat from the aluminium LED pcb, via a separate die cast heat sink to the outer body casting, is achieved by direct metal to metal contact between the two castings. This configuration creates a very small form factor that apparently achieves such good thermal management that a maximum ambient temperature of 50-degrees celsius continuous use rating is specified.

The RISE range offers a very wide array of light distributions and these are produced by fitting a secondary optic in front of the standard five-degree lens in the light engine. These secondary optics ensure that the lit effect produced is extremely smooth, although there must be additional light losses caused by these additional lenses/diffusers. To fit or change the secondary optics on site, two very long screws are loosened from the back of the luminaire body, allowing the front casting to be removed. The IP66 rating is achieved by soft silicone rubber seals between the back of the secondary optics and the primary lens. The secondary optic is clamped in place with a single central screw fixing, thus compressing the gaskets.

This detail leads to the most surprising aspect of the design, as water is allowed to run through the luminaire while apparently maintaining the IP66 rating. The rationale for this is that it allows add-on optics to be changed in a foolproof way that does not compromise the IP rating.

The front casting has built-in recesses so that the secondary optics are set back by around seven millimetres. It is understood that this detail gives improved glare and beam control. If water was allowed to build up in these recesses when the luminaire was pointed above the horizontal then it would lead to a variety of problems over time. However, channels are incorporated in the front casting allowing water to drain away from the recesses and into the luminaire body. In the sample I examined, these water channels were quite small and might tend to clog up over time with debris, but these have been increased in size in the final version. Once water has entered the luminaire body it then passes through and exits via the two fixing screw locations and the split line between the body and the rear end cap casting.

One of the most successful design details is the double action Macro Lock mechanism. This locks movement in both horizontal and vertical axes with a single screw thus simplifying and reducing the time needed for aiming.

The designers have developed the RISE range so that individual RISE luminaires can be mounted together to produce multiples each with different optics aimed independently. The singles and quad versions can be combined on the same mounting brackets to achieve very high lumen outputs. When each luminaire is aimed in a different direction the visual effect is somewhat reminiscent of Pixar’s animated robot Wall-E, but as a lighting tool there is nothing else on the market that comes close in terms of flexibility and output.

It is understood that the RISE range was designed in-house from the ground-up at EcoSense with Robert Fletcher as Lead Designer and influenced by Mark Reynoso, Paul Pickard, Cristina Rodrigues, Mustafa Homsi, Jason Kim, Jacob Hawkins, Sana Ashraf, Andy Stangeland and Elizabeth Rodgers.

The ultra short two-week delivery lead time for orders in North America is possible due to the highly modular nature of the design and the assembly location just across the border in Mexico.

RISE is a remarkable piece of design and incorporates some details that would make me a bit nervous but clearly a great deal of engineering resource has been invested in its development, which should ensure a long working life without issues.

Due to restrictions between Color Kinetics and EcoSense it is understood that no colour changing LED versions can be offered for a period of time. Fixed colour dichroic filters are available, which do provide a good selection, but the efficiency is quite low for some colours, notably blue.

The high lumen output, small size, flexibility and wide range of optics, including the very narrow five-degree primary lens of RISE should allow the range to be frequently specified and commercially successful.

David Morgan runs David Morgan Associates, a London-based international design consultancy, specialising in luminaire design and development, and is also managing director of Radiant Architectural Lighting.

Email: david@dmadesign.co.uk

Web: www.dmadesign.co.uk

Tel: +44 (0) 20 8340 4009

© David Morgan Associates 2017

Chicago Riverwalk, USA

The main branch of the Chicago River has a long and storied history that in many ways mirrors the development of Chicago itself. Once a winding, marshy stream, the river first became an engineered channel to support the industrial transformation of the city. Over the last decade though, the role of the river has been evolving thanks to the Chicago Riverwalk project – an initiative to reclaim the Chicago River for the ecological, recreational and economic benefit of the city.

As part of the initiative, the Riverwalk needed an improvement on its previous lighting scheme, which was dominated by stark, security-style lighting. The new lighting, designed by Schuler Shook, was designed to be a drastic departure from this, instead creating something more playful, interactive and altogether more welcoming.

Schuler Shook was part of the team led by Ross Barney Architects and Sasaki that was selected by the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) to create something special along the river. The firm typically works with the CDOT on the majority of its projects where creative and innovative lighting solutions are required. Giulio Pedota, Principal at Schuler Shook, was assigned the project internally, partially due to similar work experience that he had with the CDOT, particularly on the Navy Pier Flyover, a pedestrian bridge east of the Riverwalk.

After receiving the architectural and landscape design concepts from Ross Barney Architects and Sasaki, Schuler Shook developed a lighting design that was both ‘innovative and elaborate’, according to Pedota, inspired by the ‘striking’ concepts that the architectural team drew up.

“The architects had developed the concept of a series of ‘rooms’ along the river, with a unique theme for every room. Naturally, the lighting design had to respond to and reinforce these themes,” said Pedota.

“The design team wanted the Chicago Riverwalk to be an attractive civic space in Chicago, where people could explore the variety of opportunities to escape, relax, play, dine, watch live performances and see the city from a new angle that hadn’t been available before.” The initial lighting designs for the various room themes included imaginative and eye-catching lighting effects such as fire, illuminated artwork, unique pedestrian poles, tree lighting, floating illuminated buoys, lighting projections to mimic moonlight, interactive lighting effects and a dramatic set of stairs for the River Theatre.

Working along the tight space of the Riverwalk made the project fairly challenging from a technical point of view, as Pedota explained: “The design team needed to work within a tight permit-mandated 25-foot-wide build-out area to expand the pedestrian program spaces and negotiate a series of under-bridge connections between blocks.” Alongside this, the CDOT required that all fixtures be easily accessible for maintenance, meaning that some of the typical lighting design ‘magic’, such as hiding fixtures under benches, or concealing them in other architectural details, was not allowed.

However, the biggest obstacle came when having to account for the river’s annual flood dynamics of nearly seven vertical feet. Faced with a site located in a flood zone, the lighting design called for all fixtures to be robust and rated for submersible applications, while all electrical components such as wiring, wiring splices and junction boxes needed to be rated for submersible applications too. Such precautions were ‘field tested’ a few days after the project was completed when the site completely flooded, but fortunately the decision to take these extra steps was justified, as the fixtures remained lit during the flood.

The portion of the Riverwalk that underwent renovation was divided into five different themed blocks or ‘rooms’: The Marina Plaza, The Cove, The River Theatre, The Water Plaza and the Jetty, each with their own unique look. However, as the city wanted to minimise the number of fixture types and reduce energy consumption, Pedota and his team responded with fixture consistency from ‘room’ to ‘room’, and the use of highly efficient fixtures to deliver appropriate illumination levels for safety and comfort. He continued: “Considering budget was limited, the design team was constantly monitoring the cost and participating in value-engineering efforts, putting significant effort to retain the performance requirements of the project without sacrificing the aesthetic aspect of the design.”

Alongside the city planners’ needs, Schuler Shook had to factor in some key lighting considerations from the architects, as Pedota explained: “For the most part, the architects wanted to ensure that the lighting equipment was very well integrated into the architecture, for aesthetic purposes, but also to ensure that fixtures were protected from potential impact or harm caused by visitors.

“To achieve this, fixtures [from MCI Group and LED Linear] were integrated into the handrails and benches, or were installed flush with the pavement or planter walls, or were recessed in continuous floor slots to conceal fixtures from view.

“Another aspect that was important to the design team was celebrating the historic aspect of the site. To achieve this, the existing arcade piers and ornamental capitals were illuminated with in-grade fixtures [from Hydrel] to uplight these historic architectural elements.”

As there are no IP68 rated handrails in the industry, the illuminated handrails had to be custom-made in order to meet the submersible applications. To achieve this, the handrails were fitted with 3000K, IP68 LED tape with a frosted lens to protect and diffuse the light source.

In The Cove, patterns of projected tree-branches are achieved with CMH150W/T6, weatherproof, theatrical fixtures from Hydrel fitted with glass-gobos and pole-mounted at street level. While in the Water Plaza, the colour-changing LED fixtures highlighting the stone of the waterfall, along with the colour-changing fountain fixtures designed by Fluidity Design Consultants, create amusement to all the visitors, especially children. In The Jetty, the LED Linear ‘fish lights’, as the architects called the colour-changing LED lights, delineate the boundary where water meets land.

Bridges linking these three ‘rooms’ were illuminated with linear LED fixtures [from MCI Group] with opal white lenses, yielding 1.8 fc average at grade. To provide safety and comfort and to improve facial recognition, fixtures were angled five degrees to provide 1.0-1.5 vertical fc, measured at eye level. The linear LED fixtures used throughout the project use 5-watts per linear foot to delineate the paths, illuminate the ramps in the River Theatre, and provide safety and comfort.

Due to concerns the Landscape Architect had with heat from fixtures uplighting the trees, 12-watt, low-heat LED in-grade fixtures were utilised to illuminate the trees. In addition, fixtures were meticulously integrated within the stairs, at a safe distance away from the trees to avoid damage to the root systems.

The transformation of this site, from its former, utilitarian appearance to the bright, welcoming new look, is something that Pedota cited as ‘incredible, both from an architectural point of view and from a lighting perspective’. He said: “We were very happy with the translation from the conceptual approaches to the final results as seen in The Cove, The River Theatre, and The Jetty.

“In The Cove, the idea was to create a moonlight effect through the trees, very much like we do when recreating exterior scenes in theatrical lighting. This effect was going to be the general lighting of this room, and our first impression when we saw the final effect was magical! It was recreating an exterior effect in an exterior application, which made it more realistic and at the same time unexpected, given the scale of the effect.

“In The River Theatre, the series of ramps were enhanced and reinforced through a series of linear LED fixtures recessed on the riser of the stairs, guiding people up and down the staircases. This, in itself, was visually stimulating. It creates a sense of order to this entire site while providing safety and comfort.

“Last but not least was The Jetty. The colour-changing LED tape integrated at the edge of the zigzagging piers is a direct result of hearing the city’s desire to create a visual attraction after dark among the flowing wetland gardens. Because this effect was tested prior to the final installation, the design team was very happy with the results of this lighting feature. It transforms the site with its infinite, colour-changing capabilities.”

And while Pedota admitted that it would have been nice to have had more funding available to effectively execute all of the original ideas that both the architects and Schuler Shook came up with during the conceptual phase, he believes that this adds to the constant learning curve of lighting design. “We are always learning from our projects and the people we get to design with,” he said. “That is a process, and it shouldn’t be changed, or there would be nothing left to learn.”

Regardless of any budget-driven changes or restrictions imposed upon the project from the city, Pedota remains very pleased with the final outcome, and particularly with the reaction from the Chicago public and its visitors.

“What stands out is how quickly this new space in Chicago has been accepted and welcomed by people,” he said. “Everyone is drawn to it, and that speaks volumes for how well integrated all aspects of the park are, from the lighting to the materials used to the beautiful landscaping.

“Getting to light something that is for everyone to enjoy and on such a grand scale really stands out for us.”

Harbin Opera House, China

Known as the ‘Ice City’, Harbin, capital of Heilongjiang, China’s northernmost province, houses an expansive, impressive opera house. Set amongst the city’s untamed wilderness and frigid climate, the building boasts a crystal-like purity and transparency, blending in with the surrounding nature and topography.

The lighting for this remarkable structure, managed by Beijing United Artists Lighting Design, was designed to complement the architectural concept that the building grows out from the local environment and responds to the aforementioned untamed wilderness, while also revealing the purity and clarity of the space, creating an enriching experience for visitors in the process. To help them work towards this concept, the lighting team devised a motto of ‘lighting the rhythm of the frozen music’.

Beijing United Artists came on board with the Harbin Opera House project having previously worked with MAD Architects for the Ordos Museum in the Gobi desert, and Dongning Wang of Beijing United Artists, believes that this prior relationship helped create a harmonious working environment. He said: “During our work together on the former project, we had built up trust with MAD and found an effective way of communicating with each other by using the language of light.”

This trust between MAD and Beijing United Artists helped the lighting designers in the bidding process, with MAD insisting throughout that Beijing United Artists was the right firm for the job. “It was a long and tough journey,” explained Wang. “But based on the Ordos project, we were the first lighting design team that the architects were thinking of and proposed to the clients. They liked our ideas so much that they acted quite stubbornly and proposed us to the client again and again.”

Such insistence landed Beijing United Artists with the interior lighting design for the project. However the team still created a full, comprehensive lighting strategy for the whole project, from the interior to the exterior, the façade and the landscape. “We did this because we believe that to achieve a good and responsible design, you should consider the project as a whole, not just the one part that you are being told to do,” said Wang. “One thing that we are still very proud of is that we provided an interior lighting design that is seamless with the exterior, to the extent that it's hard to tell that it is done by different lighting consultants.”

Working with the concept of revealing the purity and clarity of the space, the team at Beijing United Artists devised three ways of lighting the main atrium in one piece of roof, developing a hierarchy. From this hierarchical aspect, the designers made a careful lighting plan with a ‘less is more’ concept to be more adaptive to the functions of the varied spaces, and the movement of visitors.

At the lobby entrance, a ‘welcome mat’ of light; in the middle, a super indirect light; and on the wooden shell at the end of the lobby, a vertical glow. All light fittings are completely hidden in the architecture, creating a pleasant rhythm of light unobstructed by technical details, and unplagued by hot spots or sharp corners.

The wooden shell is the focal point of the lobby; washed lighting from above gives the whole lobby a warm, inviting atmosphere, while on the canopy outside, spotlights were placed in slots, directing light on the ground to avoid reflection and allow people inside to see out.

To achieve the desired ‘purity’ in the space, it was important for the designers that guests see the light, but not the fixtures. The concept designer worked with a software expert and an industrial designer; together, this team calculated the illumination of each space, while making expert recommendations on where fixtures might be hidden. Through their efforts, visitors can explore the beauty of the space without awareness of any lighting fixtures.

To create a twinkling effect on the pyramidal glass roof, the designer selected a quarter of each faceted unit, attaching it with dotted film. Sunlight adds a twinkle to each pyramidal unit, creating different glass reflections throughout the day. At night the filmed glass is grazed from below by LED light bars, seeming to glow from within and attracting visitor attention from far away.

Within the smaller theatre, guests are reminded of the exterior of the building by a panoramic window behind the stage. This seamless connection to the outside world mimics the gleaming ripple effect of the lake outside. Narrow-beam in-ground features, carefully placed at the aisles along the walls, create the gleaming ripples of light on the walls. The irregular wall texture works with the light to create drama, rhythm and pleasing shadows.

In the big theatre, the architect called for a glowing ‘diamond’ for the owner’s VIP area above the mezzanine. Custom RGB LED fixtures are hidden behind the acrylic diamond panel and transition from starry white to warm amber, changing according to the event or the seasons.

This starry, twinkling diamond approach is replicated in the corridor connecting the basement parking plaza and the main lobby. Fibre optic lighting minimises the visual impact, but creates a dream-like grand entrance at the steps.

Although impressive, this isn't what the lighting designers originally had in mind, as Wang elaborated: “We initially designed a huge ‘cloud’ or ‘snowflake’ pendant lamp over the grand steps linking the lobby to the parking plaza. We carried out intensive studies on lightweight, fireproof materials, along with other feasibility studies, but in the end we had to make a compromise due to some of the state’s fireproof regulations. It’s a shame as MAD were very fond of the idea too, but we had to lose it and go for the fibre optic solution instead, which we like, even if it’s not what we originally designed.”

In spite of this, Wang remains happy with the final outcome of the project, even if it was more demanding than other projects that he has been involved with. He said: “For me, I feel that it is the toughest project that I have ever worked on! I want to thank the architect, Ma Yansong from MAD architects, for his pursuit of perfection, as this encouraged us to create an equally perfect lighting solution.

“Generally, we are very happy about the final effect. Whether looking at it from outside or inside, or moving from A to B inside, it presents most of our initial plans, in that we tried to create a hierarchical richness and a rhythmic mood to complement the music.

“Now, the light gives the space a poetic elegance and reveals frozen movements in time. Thanks to the open-mindedness of the people at MAD architects, they treated lighting as a very important design element when they were composing architectural design ideas. Now you can see that the lighting has become one of the most vital and poetic design treatments for the space.”

“From my personal point of view, I think it is the best combination of hierarchy and rhythm, and it is the purest lighting that I have ever done.”

Since its completion, the Harbin Opera House has gained a lot of plaudits for its stunning lighting design, most notably at the IALD Awards, held in Philadelphia during this year’s Lightfair International trade show, where it won the Radiance Award – the grand prize of the event. Such recognition was warmly received from Wang: “It is a great honour to win this internationally recognised award, and I was thrilled to step on stage to receive it.”

Wang added that while the award win was a great personal honour, he was hopeful that such recognition would have a knock-on effect for the Chinese lighting design profession as a whole. He said: “The award is a very important recognition for my more than fifteen years in lighting design. Along with my team, we were some of the very first lighting designers in China’s recent lighting history. Back when we started out, there were very few people or clients who would think of lighting design as an independent design discipline, let alone pay for our work. It took a lot of strength and belief from us to get through.

“Fortunately, due to more and more outstanding architects like MAD, and other great projects involved with more international cooperation, we have become more and more confident. I’m hopeful that this award will raise awareness of the IALD in China, and my winning experience will bring more attention to my Chinese peers in the lighting industry, as this will help the lighting industry grow very healthily and rapidly.”

Daan Roosegaarde

Before his appearance at darc room, we had a chat with Dutch artist and innovator Daan Roosegaarde, founder of Studio Roosegaarde, to discuss his approach to light, and the relationship between people, technology and space.

Explain your journey to becoming an artist.

I think I’ve always considered myself as a maker, not just a consumer, to make new proposals, to make new dreams, to make new solutions. So in a way the projects that you’ve most likely seen, the bicycle paths that charge at daytime and glow at night, the Smog Free Tower that provides clean air in Beijing, are really about triggering imagination, but at the same time, are based on a desire to upgrade reality. Maybe in the beginning we operated purely in the art and design scene, but now the scale becomes bigger. We still love the art and design scene, and we will always keep on doing that, but I think the scale will change as the studio continues to grow bigger.

You have always used technology in your art. Why is this?

Technology is a great tool to make new ideas come true. And don’t forget, technology is the things that we make to improve our lives. The wheel is an extension of our legs, the telephone is an extension of our voice, so in a way technology is an extension of who we are. What is fascinating for me is not necessarily the technology, but the impact that you want to create, the social impact. So projects like the Smog Free Project that show the beauty of clean air, or the beauty of clean water or clean energy, I think that is really what pushes us in our work.

Right now we’re more focused on biology, on nature. We’re working with light-emitting algae, one of the oldest microorganisms in the world that wake them up a bit, when you shake them, they become lights. So we’ve been growing them for the past two years, making the most light-emitting algae currently available. So there we have light and energy without a solar panel, without an energy bill, without tech. I’m really interested in biotechnology in a way, in a world where we grow things instead of build stuff.

Do you have a particular affinity towards light?

I think for me light is not about decoration, it’s about communication. So when we look at the stars high above in the sky, that’s not just a romantic image, it’s also in a way information from history speeding towards us at 300-kilometres per second, the speed of light. It’s our history, but maybe also our future, because one day we’ll go there. For me light is a great way of communicating with yourself, your body, and the people around you. It’s not about decorating but reforming, and making places that are good for people.

What are your favourite lighting projects?

We’re currently working on a series of energy-harvesting kites that fly high up in the air for several weeks. They’re smart kites that are connected to the ground with cables, and because the kite is always searching for the optimal wind, the cable moves up and down, and therefore it generates electricity – enough for 200 households, around 100-kilowatts. We make the lines of these kites light-emitting as well, so you have these beautiful dancing lights going up in the air, and at the same time they are generating electricity, the same way that a dynamo on a bicycle generates light, but a little bit more sophisticated – a lot of smart people worked on the project to make it happen. We’re launching this in November this year. It’s a design that is more about improving life, rather than just making beautiful things. For me, that is true beauty.

How did the Smog Free Project come about?

That’s a crazy project. It started three and a half years ago. In the beginning people said it’s not possible, but we’ve proven that it works, we have the scientific results from the technical university in Eindhoven in the Netherlands. So it sucks up polluted air, cleans it, releases it and makes areas that are up to 70% cleaner than the rest of the city. It’s really about the beauty of clean air, of clean energy, which I think is basically the drive of our studio. I don’t see myself as a light artist, but rather I use light and technology to show the beauty of a new world. It’s a beautiful, crazy project and I’ll make sure that I address it at darc room as well. It’s interesting also because the UK government has announced a big plan to fight against pollution, and they’re planning on making car tunnels as sort of sucking up devices to provide clean air for the city. So they’re following up our ideas, which is really cool. So you see innovation is always step-by-step. In the beginning it’s a one-off, special project, but now it becomes part of a new standard, which is beautiful.

What is the answer to the world’s problems?

There’s not a lack of money or technology, there’s a lack of imagination, so I think it’s really important that young designers, young architects, artists and engineers work together on proposals on how they want the future to look. That’s where the energy is, that’s where the finance is, where the curiosity is. We shouldn’t do less, we should do more, and just waiting for governments or hanging it as social responsibility is not going to do it. We should design the new standard. I go to New York and I see light bulbs. Light bulbs, my God! LED was invented in 1973! So everything is already there but we just have to learn how to appreciate it more and show the beauty of cities that are energy neutral. Also the notion of light pollution – why do we have street lights on all the time, even at night when nobody is there? It’s stupid. Just plug in a little sensor to make it interactive, like our Dune project, where thousands of fibres follow you with light when you walk by. Why can’t that be street lights? I hope that darc room looks at showing what is possible, and ask that question: why are we not doing this yet? That’s maybe something that we need to answer as a collective.

What is your talk topic at darc room?

I’m going to show some previous projects like the Lotus and Dune, some current projects like the Smog Free Project, and some future projects like the Glowing Nature – the algae that I talked about – and the kites, but really show how good design, good technology can upgrade a city or a landscape. I won’t just talk, talk, talk either, I’ll take some time to show, and also open up the room for some Q&A, I’m sure that there are a lot of questions. London is always eager to learn, that’s the energy I get.

Are you looking forward to darc room / London Design Festival this year? What are you looking forward to the most?

I’m really looking forward to it. I’m looking forward to meeting up and exchanging ideas, because you’re very well connected to the lighting industry, and we’re a bit on the edge of what is and what is not possible, but it’ll be nice to trigger that conversation.

We know London Design Festival quite well from last year as well, they’re great people. I love the independent pavilions that they’re launching every year, and the larger public artwork designs that they do, they’re really powerful.

To register for Daan Roosegaarde’s lecture at darc room, go to www.darcroom.com

Strasbourg Cathedral, France

The nocturnal appearance of one of Europe’s most important cathedrals has undergone a remarkable transformation, thanks to a stunning new lighting design scheme.

Strasbourg Cathedral is located in the heart of the Grande Île, an island that lies at the historic centre of the north-eastern French city and has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1988. The cathedral itself has been under protection as a heritage building since the late 1800s, and is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in France, with its high silhouette dominating the city’s skyline. Still deeply immersed in a medieval urban structure, the cathedral is the symbol of Alsace, and its four million visitors per year make it the second most visited cathedral in the whole of France, second only to the Notre Dame in Paris.

Construction on this landmark structure began in 1015 by Werner de Habsbourg, although following several fires, reconstruction of the cathedral began at the end of the twelfth century and continued until the fifteenth century, progressing from the chorus towards the western façade, and ending in 1439 with the raising of the spire. As such, the cathedral blends Roman, Gothic, Baroque, Neo-Gothic and Neo-Romantic architectural styles, and is considered to be one of the masterpieces of gothic art.

The new lighting scheme for the building was created by French lighting design practice L’Acte Lumière, working with electrical contractors Citeos, engineers Lollier and conservation architects JCBA.

The project was carried out as part of a wider, unified lighting plan aimed at revitalising the city, enhancing its heritage and creating something more attractive for tourists visiting the area through the use of light and shadow, while also inviting the Strasbourgois themselves to rediscover their city with new eyes.

The lighting for Strasbourg Cathedral reveals a new facet of the church that largely exceeds the framework for the urban area of Strasbourg. Each night, the cathedral is wrapped in a soft and balanced light and shadow. This glowing light is designed to respect the edifice and urban context in which it is integrated. It does this by magnifying the exceptional patrimonial and architectural wealth of the cathedral, such as its remarkable frontages and sculptures.

Initial specifications for the project called for a ‘highly qualitative light, revealing the iconic and magnificent architecture of one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture, while remaining respectful of its millennial history and sacred dimension’. Owing to its status as a UNESCO protected site, the team at L’Acte Lumière was required to present, account for and share their choices with the validation committee, which included the building owner, funders and contracting authorities from the city, as well as the heritage foundation itself. Designers were also required to complete a manifest stating their commitment to qualitative light as they revealed the architectural magnificence of this iconic Gothic cathedral.

During these early stages of the project, L’Acte Lumière went through a highly detailed planning process, using an incredibly complex 3D model of the cathedral to create the rendering, as Jean-Yves Soëtnick, lighting designer at the firm, explained: “It was very pleasant to work on such a highly-detailed 3D rendering, something that is not frequent on heritage buildings, to test almost every single floodlight on the Cathedral.

“Every projector had to be calculated, but while it was a huge amount of work, it was worth doing it as the day we completed the first rendering, I knew it would be fine. The rendering helped us to identify some details like complex shadows, which we were able to anticipate without spending time testing it on site.”

After deep consideration of the sacred and iconographic facets and meanings of the structure, designers chose to create a precise illumination, balancing shadow and light. The brown and yellow sandstone comprised rich gradients of red and purples, corresponding to R8 – R9 CRI. This is a difficult colour to render in high quality diodes, so designers selected a 2700K fixture with a short chromatic distortion to ensure quality light. This solution infuses a global ambient luminescence onto the structure, allowing the deep colours of the sandstone and its intricate details to be revealed.

Focal glow and highlights were used to enhance the architecture and reveal detailed layers of masonry, like illuminated text. Dynamic white LED luminaires, soft gradients and subtle tints were used to create three distinct nightscapes throughout the whole of the elevation.

These nightscapes vary depending on the time; the first, set between twilight and 10pm, acts as a ‘kind of continuity of the colours from the last solar rays’, highlighting the intricate layers of the structure, with each receding layer growing progressively warmer towards the centre.

During the second, set between 10pm and 1am, the iconographic details are reduced and blurred, to draw eyes to the elevation of the building to give a more unified view of the whole edifice at its full height, while in the third phase, set between 1am and dawn, only the upper part of the cathedral tower and roof is highlighted – immutable and comforting, it remains emergent throughout the night above the urban skyline while minimising light pollution to nearby buildings.

The lighting of the cathedral integrates the challenges of energy saving and easy maintenance. The light is produced entirely by LEDs, a first in France for a patrimonial building of such a size. As with the design of the new luminaires and their implementation, the optimisation of the energy output of the installation was one of the largest challenges for the project. However, the use of the latest LED technologies makes it possible to better target the elements to be lit, and therefore reduce total energy consumption, leading to a more effecting lighting. Alongside this, the installed LEDs have a much longer lifetime, and far reduced maintenance needs.

The installation is made up of 580 fixtures, including around 400 Lumenbeam and Lumenfacade luminaires from Lumenpulse, 30 periphery projectors, 60 devices embedded in the ground and 490 projectors or linear devices on the building, divided into eight families of devices, from 3-watts to 250-watts. Every projector is dimmable for the perfect quantities of light, revealing the splendour of the building, the distinctive colour of its sandstone and its intricate masonry and layers. These elements are DMX controlled by nine electrical power boxes that utilise Lumenpulse’s Dynamic White technology, which allows the lighting designers to tune the luminous power and colour temperature in order to precisely match the colours of the stonework.

“Throughout the project, the effects had to be correctly balanced and we had to reproduce the same effect across the building, however in some cases we had to simulate the same effect, but from different points, distance or angles,” Soëtnick explained.

“So it was important to be sure that we had the same quality of light without depending on one type of projector, so the Lumenpulse range was perfect for this.”

Elsewhere, L’Acte Lumière chose Louss for their recessed inground lighting, as they were able to make a dynamic white inground light, while Insta and WE-EF were chosen for the linear lighting.

Approximately fourteen kilometres of cable and 400 light sources are installed on the building, and the entire installation was completed without any drilling into the stone, only mortar joints – an important requirement for the project set by the heritage committee, owing to the cathedral’s UNESCO heritage status. On top of this, all of the bespoke clamping sleeves, collars, fixture corsets and luminaires were painted onsite with an accurate colour to match the stone. As a result of these considerations, the entire installation can be removed without causing any damage to the structure. None of the luminaires, except those in ground, are visible from the exterior, resulting in a balanced, quiet and ‘chiselled’ light, and a magnificent, poetic glow of the building.

“The lighting creates a very rich and peaceful glow that pictures can’t translate,” continued Soëtnick. “In a way, it's a light that you have to feel, especially in the intricate layers of masonry.”

Francois-Xavier Souvay, President and CEO of Lumenpulse Group, added: “This is a very great privilege to be involved in illuminating a building of such scale and importance. It’s architecturally and historically unique, and of immeasurable significance to the region of Alsace and the whole of France.

“We felt a great responsibility to make sure that we provided an effective, sensible lighting solution that reveals the cathedral at its very best, and that will last for many years to come.”

Soëtnick added: “For me, as a lover of the city of Strasbourg, I’ve been very interested in this masterpiece for a long time; its architecture, and its history. I’m always very proud when I see people staring at the building and finding intricate details that they never noticed during daylight.

“With this illumination, and the renewal of the ‘place du Chateau’ [completed by L’Acte Lumière in 2013], it’s a complete and vibrant heart for the city, and a new night icon, visible in a soft and chiseled light all around.”

The project itself has gained recognition on a wider scale too, picking up an Award of Excellence at the IALD Awards, while also being shortlisted for the upcoming darc awards / architectural. At the IALD Awards presentation, held in Philadelphia on 10th May, judges described the project as ‘a beautiful balance of highlighting and shadow’ and ‘an impressive technical solution – a bridge between the earth and sky, an icon of darkness and light, a monument that ignites the imagination and reveals the passion of its builders’.

Kéré Architecture

Since its inception in 2005, Kéré Architecture has been taking plaudits for its socially driven, sustainable approach to architecture.

Based in Berlin, Germany, the firm has worked on projects across the world, from Europe to the USA, and most notably in Africa, where founder Francis Kéré continues to reinvest his knowledge and expertise back into his home nation of Burkina Faso.

Alongside an ambition to engage localities in its design approach, Kéré has instilled a philosophy within his firm to provide more with less, fostering innovation and resourcefulness in the practice, using local materials, local knowledge and local technologies to create holistic and sustainable design solutions.

This quest to work closely with local communities in all phases of design, from planning to construction, is based on a belief that architecture can be a vehicle for collective expression and empowerment, and by supporting the educational, cultural and civic needs of local communities with its provocative, yet dignifying design, Kéré Architecture hopes to continue raising awareness towards the sustainable and economic issues facing populations in rural Africa and beyond.

Such passion and dedication towards improving the rural communities in Africa stems from the firm’s founder. Born in the small West African town of Gando, 125 miles south east of Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, in 1965, Diébédo Francis Kéré was the first son of the head of his village. As such, his father allowed him to attend school, even though many in the village considered conventional western education to be a waste of time.

At 18, Kéré was awarded a scholarship to study carpentry in Germany, before he made the switch to architecture, earning a degree in architecture and engineering at Technische Universität in Berlin. During his studies, Kéré also set up the Kéré Foundation, formerly known as Schulbausteine für Gando, to fund the construction of the Gando Primary School, which earned the prestigious Aga Khan Award in 2001. The Foundation is still in operation today, providing funding for a number of community projects in Gando.

Since establishing his own architecture firm in 2005, Kéré’s work has earned many more prestigious accolades, including the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, BSI Swiss Architectural Award, Marcus Prize, Global Holcim Award, and Schelling Architecture award.

Kéré has also been granted the honour of chartered membership of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 2009, and an honorary fellowship of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA) in 2012. This year, Kéré became the seventeenth architect to be granted the annual commission for the Serpentine Pavilion, and is the first from Africa to do so.

Erected outside the Serpentine Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens, the temporary pavilion serves as an opportunity for an architect to create their first built structure in England, and has previously been commissioned by the likes of Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron.

Kéré was selected to design this year’s pavilion by Serpentine Galleries’ artistic director, Hans Obrist, and new CEO, Yana Peel, as both felt the need for a deviation from ‘old ways’. Speaking to CNN, Peel said: “We wanted to build on the history but instantly also create a new phase of invention and experimentation.”

“We were very interested in how his practice has evolved over the past few years into being this socially engaged and ecologically engaged practice,” added Obrist. “From our very fist meeting he was very interested in thinking about the Royal Park and how you link people to nature, and how you provoke a new way for people to connect with each other.”

Kéré’s pavilion, as with a lot of his work, takes inspiration from his African heritage; the pavilion’s colour and the way that it lights up at night is a reference to his childhood in Burkina Faso, while the form of the canopy is informed by a tree in his home village of Gando.

At the unveiling of the pavilion earlier this year, Kéré said: “Where I come from, a tree is often a public space. It can be a kindergarten, a market, a gathering place for everyone. The idea was to create a huge canopy that allows the visitors to feel the elements while being protected. It is enclosed by wooden blocks that are perforated, allowing the air to circulate, which create comfort inside.”

The pavilion’s slatted timber roof is lined with translucent panels of polycarbonate, keeping rain off visitors, while allowing light to filter through. Meanwhile its funnel shape is intended to direct rainwater into a well in its centre, which is then dispersed underground to the surrounding park.

The main structure of the oval pavilion is made up of triangular sections of deep blue wood, creating a design of v-shaped perforations. This rich, indigo blue colour again has strong links to Kéré’s culture. “Blue is so important in my culture, it is a colour of celebration,” he said.

“If you had an important date in my village, there was one piece of clothing everyone was going to ask for. So when I got the commission for the pavilion here in London, I said: I am going to wear my best dress, my best colour, and that is blue.”

The lighting design for the pavilion was a collaborative effort between Kéré Architecture and AECOM. Lit from within by strips of lights in the structure’s canopy, it is intended to act as a beacon for celebration. “In Burkina Faso, there is no electricity. At night it is dark, so what happens often is that young people go to elevated points to look around and if there is light, everyone goes to that place, and there will be a celebration,” said Kéré. “That is what the pavilion will be at night – shining to attract the visitors to come and celebrate.”

Project Architect for the Serpentine Pavilion, Blake Villwock, added: “The canopy in the pavilion functioned as both a filter for natural daylight and also the source for illumination in the evening. Both functions emphasised the canopy as an important element of the design, from within and from a distance.

“At night it becomes a glowing beacon for the city. In this way, we are interested in how the natural and artificial can be integrated in the built and natural environments. I think architects can really help to push these sorts of ideas forward and challenge the discipline to innovate.”

Villwock added that the teamwork on show across all aspects of the project helped to make it such a hit. “The success of the pavilion truly is the result of an incredible collaboration of the Serpentine Gallery, our engineers and the fabrication crew. We are forever grateful to our entire team,” he said.

“The Serpentine program is notorious for its quick turnaround of sketch to fabrication to opening night,” Villwock continued. “We were approached last October to submit a proposal where we flew through two weeks of conceptual design. The concept largely came from a sketch Francis drew during a late night workshop.

“Shortly after we won the commission, Francis and I were on a plane to London and a train to Yorkshire to start workshopping ideas with our team of engineers at AECOM and fabricators at StageOne.

“The brevity of the project led us to use a simple palette of materials that were innovated using the latest digital fabrication technology. It was always important to us that the pavilion seemed handcrafted, yet precisely detailed. Development of models and full-scale prototypes was an essential part of the design process where many aspects of the engineering were unprecedented. Throughout the process, David Adjaye [one of the architects on the panel that selected Kéré for the commission] was very encouraging as a design consultant to keep pushing the boundaries.”

Villwock, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has been working at Kéré Architecture since 2014, and as project architect, liaises between Kéré and the firm’s clients, engineers and fabricators for English-speaking projects. He has also led design teams for a number of other projects in Africa and Europe, including in Germany, Uganda, the USA, the UK and Burkina Faso.

And he explained that while the firm, currently made up of thirteen architects and designers, has projects spanning several continents, Kéré remains deeply involved in every project, keeping in regular contact wherever he is in the world.

“Francis is very focused,” he said. “Projects around the world force him to spend much of his time traveling and away from the office. But having said that, we are in constant communication every day. The design process could take place across continents; sketches and feedback will bounce across many time zones.”

Kéré’s main passion though, lies in the work that the firm does in Africa. “Francis is more hands-on with projects in Africa, especially in Burkina Faso, where he is driving the construction and research on the ground,” said Villwock.

“For sites in Africa, he devotes a lot of time on-site coordinating with the local workforce and community; he is not only introducing schools for local children but also creating opportunities for training locals in construction.”

This passion for more community-led projects in Africa has rubbed off on the rest of his team at Kéré Architecture, as Villwock revealed that, while their African projects may be more technically challenging, the rewards can be greater in the end.

“Our Berlin team approach all projects in a thoughtful way,” he said. “Of course, there are more constraints when designing in Africa. It’s more challenging but this also brings unexpected potential for creativity.

“From my experience, the impact made in the African projects is often times much greater and so there is a strong sense of responsibility over just trying to be fashionable. Each project initiates an opportunity to inspire. The community is usually more receptive and appreciative to new ideas, which leads to a richness in the designs of these projects.”

Kéré Architecture’s community focus isn’t restricted to the likes of schools or community centres either, with the firm currently in the process of designing the new National Assembly of Burkina Faso, in the country’s capital of Ougadougou.

Replacing the one set on fire during the 2014 revolution that freed Burkina Faso of dictatorial rule for the first time in more than three decades, the new structure will ‘scale up the village dynamics while bolstering national identity’.

Villwock added: “In the design of the new National Assembly of Burkina Faso we introduced a new public space in the stepped façade where the community can come together and interact with their parliament in a completely new way. The pyramidal shape becomes a monument where citizens, many of whom have never seen a view higher than the treetops, can climb and have an elevated and new perspective of their city.”

Alongside this impressive new structure for the National Assembly, Kéré Architecture is currently working on a number of projects a little closer to home, including a cultural centre near Tunis, in Tunisia, an installation for a fashion show during London Fashion Week, and a temporary theatre in an aircraft hangar at Berlin’s historic Tempelhof Airport.

Kéré Architecture’s style has been described as ‘characteristically stripped back’, with a ‘frugal simplicity’. However Villwock doesn’t believe that they strictly confirm to a signature look or ‘style’, instead focusing on creating something new and unique in each project.

“I wouldn’t say that we have a signature style, but in every project our philosophy is to add value through design,” he said.

“The architecture is extremely complex. There is an immense amount of effort and research that goes into our work at all scales. Through each project, we are trying to push the boundaries in terms of performance and engineering. In terms of the ‘stripped back’ aesthetic, we try to be effective in the most economical way using locally sourced materials. Nothing is ornamental; every detail serves an important function.

“Francis constantly challenges us to work towards unprecedented design. The architecture of course serves its function, but it should always strive to be unique.”

Regardless of whether the firm has a signature look, there is a recurring theme of creating projects for the community and utilising nature in the work of Kéré Architecture, and this extends to the firm’s approach to lighting, as Villwock explained: “Light is the way nature comes into a space, it plays a huge role in our design and methodology.

“The architecture needs to negotiate the amount of light that is present in the space. In Africa for example, the design usually focuses on shading the interiors due to the hot temperatures. In places like Britain, we can embrace and try to enhance the effect of natural light.”

But while he believes that lighting plays a major role in the firm’s design, Villwock said that it is unlikely that they will introduce a lighting department within the company, instead preferring to continue working with local specialists on a project-by-project basis.

“Part of the joy of our small office is that we really benefit from the knowledge and collaboration of experts and designers,” he said. “With the broad range of projects that we do in all areas of the world, it is so important to engage with local specialists in all aspects of design, including lighting.”