Project Focus - Botree Hotel, London, UK

https://vimeo.com/1092735344

Michael Curry from dpa lighting consultants and Melanie Knüwer from Concrete Amsterdam sit down with Matt Waring to discuss their joint efforts on Marylebone London’s stunning new Botree Hotel, which combines vibrancy and uncompromising standards with a purpose-driven ethos to create a hotel where luxury meets conscious choices.

TUI partners with Signify on store lighting

As part of a wider commitment to reduce its environmental impact, travel company TUI has begun upgrading the lighting in its UK and Ireland retail branches, aiming to improve energy efficiency and support its long-term sustainability goals. Signify’s 3D-printed lighting offered a circular solution, perfectly aligned with TUI’s sustainability agenda.

With over 300 travel agencies across the region, TUI sought a lighting solution that could help deliver a welcoming in-store experience for customers while aligning with its ambitions to achieve net zero emissions and adopt circular business practices by 2050. The company partnered with interiors specialist John Worth Group to design and deliver the upgrade, with electrical wholesaler CEF supporting the supply and specification process.

A key requirement for the project was to reduce energy consumption and material waste without compromising on lighting quality. After evaluating several options, the team selected LED and 3D-printed luminaires developed with recycled and bio-circular materials. These products were custom designed using Signify’s MyCreation online configurator, which allows customers to visualise their lighting configuration as they go. This allowed the lighting to meet the visual and technical needs of TUI’s retail environments and was produced closer to the point of installation to help reduce transport emissions.

The first phase of the rollout included lighting installations in five pilot stores. A mix of panels, rafts, track lights and spotlights was used to provide tailored solutions for each space. These were configured through a digital platform to streamline design and ordering.

Karen Darler, Regional Property Manager at TUI, comments: “We are delighted with the new store lighting, which provides comfortable light levels for customers and staff, while creating visual interest in line with our TUI branding. Meanwhile, the lighting installed attributes to our 2050 net zero target through efficiency and waste reduction, thanks to excellent collaboration and teamwork. The process has been exceptionally smooth, with the projects delivered perfectly on time and within budget.”

With the initial pilots successfully completed, TUI, John Worth Group, and CEF are continuing to collaborate on the next phase of the rollout, which will see the lighting upgrades extended to an additional 30 stores.

Pharos announces New Regional Sales Appointment

(EMEA) – Lighting controls manufacturer, Pharos Architectural Controls has appointed John Jarrard as Regional Sales Manager for the Middle East, marking a strategic addition to its global sales team.

The appointment forms part of a wider initiative aimed at increasing market engagement and strengthening regional support for partners and clients. Jarrard will be responsible for driving commercial development in the Middle East, contributing to Pharos' long-term growth objectives.

Jarrard brings more than a decade of experience in architectural lighting control systems. He has held senior sales roles at ENTTEC and Advatek Lighting, managing operations across Europe and the Middle East. Alongside his industry background, he recently completed an Executive MBA at Cranfield School of Management, following a Master’s in Politics and Contemporary History.

Commenting on his appointment, Jarrard says: “It’s a career highlight for me to be joining the Pharos team. I’m looking forward to the new challenges this role will bring, while being able to leverage the skills and relationships I have from my previous sales positions. I’m looking forward to championing the Pharos products, as I can already see the significant benefits these solutions bring to a range of projects.”

Simon Hicks, CEO of Pharos Architectural Controls, adds: “We’re delighted to have John on board to expand the capabilities of our sales team. With his strong background in sales within our industry, we’re confident he will be a great asset, and he’ll no doubt bring new ideas and perspectives to our sales team.”

In Conversation with Conran & Partners - The Art of Layered Lighting

https://vimeo.com/1092737372?share=copy#t=0

Hannah Miragliotta, Senior Designer at Conran & Partners, discusses the art of layered lighting with [d]arc media Editor, Matt Waring. Exploring how lighting in hospitality spaces transforms guests’ experiences and influences mood.

More than one way to skin a CAT

In this issue, Irene Mazzei, PhD, and Tim Bowes team up to speak to a range of professionals across the supply chain to assess the challenges faced in realising a Circular Economy.

During the last five years the lighting industry has seen a rapid increase of awareness around sustainability and circularity topics: what once was only a desirable feature is quickly turning into a must-have in product design.

Numerous lighting manufacturers have embraced the concept of the circular economy (CE) and evolved their design and business operations to make their products more circular – but something is missing. Circular approaches in projects and installations are still met with uncertainty and a slower uptake, in favour of more conventional ones. Business models need to be made more efficient and competitive, so that re-using, repairing, remanufacturing and repurposing a luminaire becomes more attractive than procuring a brand new one.

How do we develop not just the push, but also the pull? How do we get other stakeholders in the value chain – up and down stream – to understand and realise the possibilities and move away from the current mindset and approach?

What is the circular economy?

Today our industrial economy is ‘linear’ by design. It is set-up to encourage us to consume and buy new. We extract material from the ground, we process it, we consume it, and we dispose it – and then start all over again. However, there is an increasing acceptance that this approach cannot continue. If we carry on as we are, it is projected we will be extracting between 170-184Gt/year by 2050, roughly double what was extracted in 2016 [1].

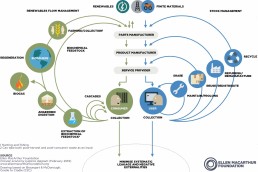

The construction industry has a significant focus on carbon reduction; however, with 55% of today’s emissions being addressed by renewable energy and energy efficiency, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation highlights that the CE will play a key role in reducing the remaining 45% of emissions [2].

It is fundamental that we collectively accept that transformative change is needed if we are to continue to have an economy that can support future generations. However, with the built environment being one that “hinders transformative change” [3], this may be easier said than done.

The CE is “an economic system that is restorative and regenerative by design” [4]. Representing an alternative approach, it asks us to look more holistically to balance the needs of the environment, business and people. It is based on three key principles [5]: eliminate waste and pollution; circulate products and materials; and regenerate nature.

It is the second principle that this article hopes to explore. How do we look to release the value of the work we are doing with product design not just today but also in the future?

How does the Circular Economy add value?

In lighting we are working with materials that are defined as within the CE as ‘technical nutrients’. Using the Ellen Macarthur Foundation’s butterfly diagram (Figure 1) we can show how different circular approaches can add economic value. The smaller the loop, the greater the social, economic and environmental value is there to be retained. But how do each of these stages allow us to realise this value? Figure 2 provides a brief overview of each of these loops.

The objective of this article is to gather the opinions of different professionals on the common challenges and opportunities associated with realising some of the wider systemic and business changes needed to truly realise a CE not just today, but also in the future. We interviewed manufacturers, designers, industry associations and contractors, the latter providing insights on the downstream value chain’s own perspective on this topic. The next section contains contributions from Nigel Harvey (Recolight – Luminaire recycling provider), Paul Beale (18 Degrees – lighting designer), Benz Roos (Speirs Major Light Architecture – lighting designer), Ali Kay (Stoane Lighting – manufacturer) and James Ivin (Overbury – fit-out specialist).

Stakeholders’ Inputs

The first question we posed our interviewees was about the extent to which circular thinking features in their projects, and whether circular approaches are being developed in their practice. We also asked what they think can be done to implement more circularity in projects:

Manufacturer: “In the last five years we have seen several projects where facilities managers and building owners have taken proactive steps to convert halogen products to LED technology. While feature chandeliers or pendants are the most likely products to be viable for remanufacturing, we do see more adoption of remanufacturing of small or more standard lighting equipment. In those cases, this needs an engaged stakeholder and project team who are looking for these opportunities and we can work with them to present the business and sustainability case for a remanufacturing approach rather than replacement; this is done through LCA (Life Cycle Assessment), embodied carbon calculation, energy saving calculations.”

Lighting Designer: “Circularity is becoming an increasingly integral part of our conversations with clients, though its implementation remains highly project-specific. While new-build projects or Cat A refurbishments typically default to installing brand new luminaires, we are actively exploring opportunities to re-use and repurpose existing equipment, particularly where the client has a strong ESG agenda or where there is alignment with broader sustainability goals. That said, the re-use of luminaires remains the exception rather than the rule. This is not for lack of interest, but because most commercial developments – especially in the speculative office market – prioritise design uniformity, perceived newness, and programme certainty. Nonetheless, we continue to advocate for re-use wherever feasible, for example by salvaging luminaires from one floor of a building and redeploying them elsewhere on the same estate, or by specifying modular lighting systems that allow for future disassembly and redeployment. We are also increasingly collaborating with manufacturers and remanufacturing partners who can support quality assurance, compliance, and performance testing to make re-use viable in real-world applications.”

Lighting Designer: “We are trying now to start with making inventories of existing equipment on projects to see how we can take things forward. Repairability is not so much on the mind of clients. If you are lucky enough to speak with people in charge of maintenance, that it is very much part of the discussion. For example, this morning we presented a scheme to a museum and the maintenance person was in the meeting, so circular products do get the preference. We have recently finished a first circular project in which we have actively refurbished 70% of the equipment.”

Luminaire Recycling provider: “Designing and manufacturing new products to CE principles largely results in potential or future circularity. The circularity is only fully realised if/when the product is reworked or upgraded, which should be many years after supply. But the urgency of the climate crisis and the need to decarbonise now means we need circularity today. An even better outcome is, where possible, to reuse and upgrade existing fittings, rather than replacing the entire fitting. Clearly upgrading with a high efficiency light source is essential to making this strategy deliver carbon savings.”

Contractor: “Contractors are inherently risk averse, so there is a conundrum of suggesting changes, which may not always be well received or could add time onto programmes and create more redesign work for the whole project team. We are putting processes in place from the tender stage to identify elements for reuse as early as possible and drive connections amongst projects internally and externally, to ensure luminaires are used for their intended purposes.”

We also tried to explore the reasons why a design originally made following CE principle may change, and which aspects can hinder its development:

Manufacturer: “In our experience, it’s the projects where the stakeholders, especially the lighting designers/architects and building owners, are looking to embed lower impact and circular principles from the outset of the project that are most likely to stay the course. it takes a committed team of stakeholders who back the approach, as different things need to be considered – like safe removal of equipment, transportation, and storage of equipment while other renovations happen. In some cases that barrier can be related to perception around remanufacturing, perhaps that it represents a less attractive/safe/reliable solution. These perceptions are often unjustified, with remanufacturers offering new warranties and by necessity with no difference in terms of safety, reliability, or compliance. It’s also true that, sometimes, the financial argument doesn’t stack up due to low numbers, in these cases the administrative costs associated with design, testing, compliance and the remanufacture taking legal responsibility for that product cannot be justified by the client.”

Lighting Designer: “The gap between circular design intent and delivery remains wide. Even when circular strategies are explored during concept design, they often fall away during procurement or value engineering. Clients and contractors tend to favour products with known lead times, warranties, and minimal perceived risk. Consequently, circular lighting options – particularly those involving remanufacturing or second-life products – can be seen as adding complexity or introducing liability. One key barrier is programme alignment. The timelines required to extract, inspect, and recertify existing luminaires often don’t fit neatly into fast-track construction programmes. Furthermore, remanufactured products rarely appear on approved supplier lists or design guides, limiting their uptake by main contractors and M&E consultants. We’ve also encountered resistance due to ambiguity around compliance, especially with emergency lighting and testing requirements. That said, the conversation is shifting. More clients are asking the right questions, and manufacturers are beginning to offer luminaires designed for multiple life cycles. But scaling this up will require structural change, not just design enthusiasm.”

Lighting Designer: “Costs and architectural design are the biggest barriers. In the end, most architects still prefer aesthetics over environmental impact. This is especially true for encapsulated products. In a recent project [7] we managed to install LED channels which can be repaired. Throughout the process we had to justify it, because it would be so much easier to use flexible LED tape, which cannot be repaired.”

Luminaire Recycling provider: “Reuse is more “circular” than replacing old fittings with new. But all too often, reuse is not considered during a project. Reuse of the product that will be displaced by new product is frequently an afterthought. And by that time, it is almost always too late to ‘rehome’ or find another reuse option for that product. This just one of the reasons why it is better for designers to seek to reuse existing product rather than specifying new. It does require a different approach to creativity – a ‘creativity of constraint’. But we really do need that change if we are to embed circularity within our industry. We also need a change in the ‘standardisation’ and ‘perfection’ mindset when considering projects. Do we really need exactly the same fitting on every floor of a ten-storey building? Does every fitting need to be completely free of surface defects and blemishes? That standardisation and perfection is the enemy of circularity.”

Contractor: Reuse targets may be implemented from the concept stage, but aspirations can also be dropped later and be included in the contractor’s tender package around Stage 4. Supply and demand are not aligned in the current market; what compromises are the designers willing to take based on the level of risk and impact, to avoid major disruptions within the project? Which brings the most common barrier: time. The reuse market remains much slower than the conventional one (buying new and with guarantee of stock).

Finally, we asked which inputs would be useful to have from other stakeholders in the industry to facilitate the adoption of not just circular products but of circular business models:

Manufacturer: “With some exceptions, I believe it’s fair to say that for the most part it’s not common that original equipment manufacturer, or lighting design professionals, are still involved in a project after completion. It is very likely that maintenance team responsible for the installation will be reactive, fixing or even replacing luminaires as and when they fail. Planned collaborative efforts between stakeholders could lead to more circular projects with appropriately timed and planned interventions that maximise luminaire lifetime and keep lighting designs true to the original brief. While we already see the emergence of business models such as lighting as a service and guaranteed luminaire buyback schemes, I see potential for other manufacturer business models such as luminaire health checks at planned intervals. I also see the potential for through project lifetime professional lighting design consultancy services where lighting professionals can perhaps quantify lumen depreciation, and colour shift alongside surveys and advise on appropriate actions to keep schemes compliant and designs faithful to original intent.”

Lighting Designer: “To enable circular business models, we need aligned commitment across the value chain. From developers and landlords, we need clear client-side ambition – ideally written into the brief – to prioritise re-use and reduce embodied carbon. From manufacturers, we need transparency around product origins, disassembly protocols, and the availability of testing or re-certification services. From contractors, we need willingness to collaborate and a shift away from risk-averse procurement practices that default to “new equals safe.” Perhaps most of all, we need data: environmental, performance and cost benchmarks that demonstrate the tangible benefits of circular design in real terms. Only then can circularity be judged not as a well-meaning exception, but as a rational default.”

Lighting Designer: “The biggest hurdle is that operation / maintenance teams are mainly not part of the design teams. This attitude needs to change to make a difference.”

Luminaire Recycling provider: “As the electricity supply grid continues to decarbonise, so the role played by embodied carbon will become correspondingly larger. So, we need to see more commitments from purchasers, specifiers, and public procurement bodies to prioritise reuse over new, where this is technically feasible without compromise to energy efficiency.”

Contractor: Lighting designers should allow for less specialist areas to be open for reused luminaires. Manufacturers should have take-back and refurbishment services, map materials, and keep track of where their products end up. Local authorities should offer up safe storage space in case project timelines are crossing over. Projects should allow for more time so that more reuse options can be explored. The industry should collectively commit to minimise what goes in spaces (e.g. CAT A).

Conclusions

Without systemic and significant change, even the most “circular” product will follow the current linear model, and will end up being discarded when no longer needed within a project. If we are to realise the CE, we must start working out how we enable the various circular value loops.

This does not (only) come down to product design, and a single “one size fits all approach”; it does require business and approach change. Common themes that could support this have been highlighted by stakeholders in this article, including:

- Having an involved and engaged team in a project

- Incentivising client buy-in

- Planning maintenance efforts throughout the lifetime of the project

- Embedding flexibility in installations and allowing for “creative constraints”

- Supporting digitalisation efforts as a key opportunity for wider stakeholder involvement

But, most importantly, collaboration across industry is crucial – both within the lighting industry and with external stakeholders.

The dialogue is already open in the lighting industry and events such as the upcoming Circular Lighting Live 2025 conference or the 2050 Connected conference are a great opportunity to start exploring possibility across the value chain, to be able to overcome some of the barriers that separate the industry from a truly circular economy.

Making the Invisible Visible: Google x Lachlan Turczan

Returning to Milan Design Week for 2025, Google once again collaborated with light and water artist Lachlan Turczan for Making the Invisible Visible, an immersive exploration of the ways in which art and design can be seen as acts of alchemy that bring ideas to life.

With Making the Invisible Visible, Google sought to show how abstract ideas can be translated into tangible forms to be felt and experienced, through Turczan’s artwork, and the design of Google’s latest hardware products.

On entering the exhibition, visitors saw Turczan’s latest artwork, Lucida (I-IV), a series of spaces sculpted entirely out of light. These luminous vessels ripple through mist, forming shifting environments that blur the boundaries between the tangible and intangible. Light – typically a fleeting, ephemeral presence – takes on a material permanence, transforming into something that can be touched, inhabited, and felt, bending, flowing, and responding with fluid dynamism to the interaction of the viewer.

Making the Invisible Visible marks the second time that Turczan and Google have collaborated for Milan Design Week, with the two having previously worked together for Shaped By Water in 2023 after Ivy Ross, Google’s Chief Design Officer of Consumer Devices, became inspired by Turczan’s artwork.

Speaking exclusively to arc magazine, the artist recalled his early interactions with Google, and how this blossomed into the collaborative relationship they now have.

“Ivy Ross first saw my work in 2021, when I was making sculptures with water and mirrors. The Google team was heavily drawing inspiration from my work, and at a certain point, they had so many images of my work on their inspiration boards, that Ivy said ‘I have to meet this person’. She reached out to me and commissioned me for the collaboration in 2023. They found something that they liked in my work, and then created a story around it. In 2023 it was perfect, as they had designed a watch that was inspired by the form of a water drop, so formally there were strong similarities with my work.

“Fast forward to 2025, I’ve been doing a lot of work out in the landscape, creating light sculptures in the open air, where I found bodies of water, and I would arrest light through either the silt in the water, or steam coming out of hot springs. I shared some of this work with Ivy, and she asked how I could bring this inside and share it in a gallery or museum context.

“I had some sketches that I thought were possible, but it required a significant amount of time to engineer it. We made a couple of small maquettes and prototypes, and Ivy gave us the go ahead – she is the kind of person who really knows what the world is wanting, so it’s incredible to have her as a sounding board for creating this work.”

Through his landscape work, Turczan explains that each piece was set up in a way that would appear from a specific vantage point, where the focal length of the human eye would create an illusion where the conical aspect of the light would become parallel.

“As things come closer to you, in your vision they flare out, so it required a very specific stance to soften your vision. Therefore, this thing that you know to be immaterial, that you know to be made of light and coming at you in a space can take on the feeling of a monumental thing that goes infinitely into the sky and appears to be architectural, because of it being parallel.

“Traditionally, light is either diverging or converging; it is either illuminating something, or creating an image. We rarely ever have the opportunity to experience parallel or laminar light. In the same way that when you turn on a faucet and the water coming out can appear completely glassy, with the molecules moving in the same direction, we had that idea of coaxing light into a regular and consistent pattern.”

Complementing this visual effect, another integral facet of Lucida (I-IV) was its interactivity, and the way that, by passing through these laminal curtains of light, the viewer could shape and impact the “flow” of the beams.

Turczan continues: “Once we had the opportunity to experience parallel light, the next step was how do we interface with and move through it? Ivy wanted the piece to be responsive, to be something that we could engage with and physically interact with.

“The ability to feel like you’re touching the light, reaching out to this substance that you know, logically, is immaterial, but that moves and makes sound based off of your motion, is responding to you, these are triggers and cues that trick the brain into thinking that you’re dealing with physical mass.

“I’m really inspired by the Light and Space movement that came out of Southern California in the 1960s – artists like Helen Pashgian, Robert Irwin, and James Turrell. These artists had a focus on perception and on immateriality, how light inhabits a space, how light can shape space and define experience. However, with their work, it was either passive or you enter a realm that the artist has created, without being an active participant, other than through your perception.

“I have quite a complicated relationship with interactive art, which has often felt to me like you press a button, and then this thing does something, which isn’t natural. If I can touch it, that is the highest ideal of interaction – the idea that you can create an object or a substance. That became my ethos for this: to imbue light with physical characteristics, so that it’s almost less of an interactive art piece and more of a meta material, if you will, this idea of pushing the qualities of substance through the way that you engineer it, becoming a huge dance and balance of optics and software and so many technical things, but at the end of the day, you have this physical object.”

To bring this piece of art to life, Turczan purchased eight tonnes of optical grade acrylic – the kind used in aquariums, which were then shaped by a military-grade fabricator into six ocular lenses, each measuring six feet in diameter.

“If you imagine a triangular prism, we took that and wrapped it around – the technical term for this would be an annular optic.”

Through these annular optics, laser projections create the kind of caustic effect that one sees when light passes through water, but extruded in space – a juxtapositional marriage of nature and technology.

The installation formed the first part of a wider exhibition from Google; from Lucida (I-IV), the experience shifted from artistic expression to the practice of design, as guests moved into new spaces that highlighted the story behind a particular Google hardware device.

Each experience looked to illuminate how an abstract idea can be translated into a tangible form – from its Nest thermostat, to its new earbuds, which used laser scans of ears to create its most accurately modelled earphones to date.

Although treated as a separate commission, Turczan believes that there are links in approach that connect the artwork to the wider exhibition. “The way the narrative is told is that there are these technologies of human reciprocity that are part and parcel of the work that Google does – the use of software and lasers, as examples. And then the work that I do uses similar technologies in an artistic way. Although we’re not using any Google technology in the work that I do, there’s a parallel in our principles. The wider piece therefore acts as a celebration of the ways in which art and design are both articulations of similar concepts.”

The installation was one of the highlights of Milan Design Week, with enormous queues for the majority of the week, and looking back at the event, Turczan says that he is humbled by the feedback that he has received, and he is excited about where to take it in the future.

“We had an incredible response. It has been remarkable to see how much the work resonates with people,” he says. “Where I want to take this work is to have this be architecturally integrated, to create opportunities where this is situated within the framework of a space, and can affect people of the long haul in a deep and meaningful way.

“We’re also in talks with museums, light art festivals, and other shows to take it on the road. We’re speaking to many different institutions to have the experience of these sculptures and get them out there. That’s the incredible thing about Milan Design Week, it’s a huge sounding to the world – everyone pays attention to it, so it has been a dream come true to have this premier there alongside Google.”

Thames City, London, UK

A former industrial site, turned luxurious, 10-acre, mixed-use development, Thames City brings a healthy dose of greenery to London’s Nine Elms. arc speaks to Foundry about the site’s lighting design, following its Best of the Best success at the [d]arc awards.

In Nine Elms, London, a stone’s throw from Vauxhall, and the recently revitalised Battersea Power Station, lies Thames City – a 10-acre, former industrial site that has been transformed into a landmark, residential-led mixed-use development.

The development, for which Phase 1 was completed last year, signals a vibrant new chapter for the area, establishing Nine Elms as a global destination in its own right. Distinguished by a stunning collection of landscape spaces, including courtyards, green podium gardens, and an expansive linear park, Thames City features a series of beautifully designed green spaces, ideal for outdoor recreation, while a thoughtfully planned network of waterside walkways, cycle paths, and green areas looks to promote active lifestyles and enhance the wellbeing of those who visit.

Alongside the lush and verdant landscaped areas, Phase 1 also features two new towers – No. 8, and No. 9 – standing at 35 and 54-storeys tall respectively, from a two-storey podium. These buildings offer new, luxury riverside apartments, and a host of resident amenities, including wellness facilities, a 30-metre-long swimming pool, residents lounge, cinema, karaoke rooms, private dining, and a sky lounge.

The initial lighting masterplan for this site came from Equation Lighting, who having previously worked on neighbouring sites at Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms, looked to create a unity across the exterior green spaces.

Keith Miller, Director at Equation, reflects on the early stages of the project: “There is a large green space that connects Battersea Bridge to Nine Elms, and we were involved in a lot of the development here, so we were well placed to come into this project as lighting consultants. The whole development was divided into two phases – Phase 1 was the three towers and the podium, while Phase 2 was a series of buildings along Nine Elms Road.

“This meant that there was a continuity. Externally, we could have the same philosophy in all of the different developments, and part of the idea of the masterplan was that it was one linear park – even though there were four or five different developers, in terms of the experience of the users, it would be a seamless journey where you could walk from Vauxhall, through Battersea, and into Nine Elms, and everything externally feels of a piece.”

Following this initial concept masterplan created by Equation, the client employed D&B contractor Midgard, who in turn brought in Foundry to realise the lighting design for the site alongside the client team and wider design partners of architects SOM and landscape architects Gillespies.

Speaking to arc, Neale Smith, Director at Foundry, takes us through their beginnings on the project, and how working off a pre-existing masterplan affected their approach. “Equation created a concept, which formed part of the employer’s requirements, and we were given this just after our appointment. We looked at this, and the initial strategy on how they saw the space at that stage, and then it was our job to build upon that. We looked at where we could deviate, and how we could work with the design team and the client to make it a more robust deliverable.”

Ellie Cozens, Design Director at Foundry, adds: “The masterplan and the information that we were provided gave us a good framework to work with, and the client was very open to building on it. As the space has evolved and as we got to learn more about this development, as it is quite complex with the towers, the podium level, and the landscape areas, the scheme took on legs of its own and evolved over the course of the project, as you’d expect.

“We used the masterplan as a framework – it is something that the client had agreed to, and the principles were very much there. Our job was to look at it and work out how to deliver it, which is often the hardest part of the job, especially with contractors and design and build, and value engineering, and all of the other challenges that we know. We looked at how we could make the space functional, while also maintaining a level of quality and lit effect that we wanted to see in the end product.”

With Equation’s initial concept masterplan in place, the team at Foundry looked at how they could elevate this further, examining primarily the ways in which people were going to be using the myriad exterior spaces, and the ways in which they each came together.

“It was all about the guest experience, and that experience after dark, because it is in the middle of a quite recently built-up area. Although the podium is completely resident-owned, the landscaped areas are open to the public,” Cozens continues.

“From a light point of view, it had to be safe, it had to be functional, we had to tick those boxes – but we also wanted a space that not only did that, but also encouraged people to dwell there and actually enjoy the space after dark. Especially in London, where there’s very few spaces like this that visitors can feel safe in and actually want to enjoy.

It was fun to be able to create those moments – it gives people a chance to take a beat.

“We did this by using lighting that was a lot more low level, more focused on functional pathway pools of guiding people through spaces. It’s not about overlighting it. We worked really closely with Gillespie and understanding all of the foliage and the planting, and how that would evolve over the seasons.”

To further emphasise the feeling of evolution and growth, Foundry utilised tunable white lighting throughout, carefully balanced to show the space transforming over the course of an evening, rather than a single static image.

“It turns it into something that you want to wander through, see what’s going on and enjoy it,” Cozens adds.

“That was very much a focus for us, and came to be a focus for the clients as well – to make it a space that people could enjoy and want to spend time in, not just transition through.”

With one of the primary goals of the landscaped areas being to promote active lifestyles and enhance the wellbeing of those using the space, the tunability of the lighting helps to contribute to a sense of tranquillity.

Smith explains: “As a visitor, you’re effectively in the middle of Vauxhall, but when you’re sat on the podium, it’s a very calming experience. All you hear is rustling leaves. If you really focus you might hear cars and sirens in the distance, but when you’re up there, everything else seems to zone out.

“It’s the same when you’re going through the landscaped areas too; there’s waterways, there’s little parks, and it’s all about making people stop and think.

“Whether you’re hearing the movement in the water, or where we have light grazing across it, picking up the ripples, we wanted to create a more sensory, intimate environment across a large scale. We did this by focusing on low level lighting, but also by concealing columns in places where you weren’t seeing where the light was coming from, and also using the buildings as a backdrop, where these are framing the pedestrian routes.”

The low level lighting also contributes towards the dark sky considerations of the project – a fundamental aspect for all landscape lighting projects to bear in mind. How Foundry tackled this was by taking the time to think about where, and how much light was needed.

Cozens adds: “We wanted to make the lighting purposeful. Something that we did quite successfully on this project was define what we actually needed from the lighting. We challenged what you might typically do, especially with regards to street lighting on the surrounding roadways. We looked at the categorisation, but dug into it a bit further. We knew that we needed uniformity, but we asked ourselves if there was a cleverer way of doing things? Is there a better fitting that directs light downwards, that is not overly bright or reflecting light upwards?

“It was the same with the façade lighting as well. Although the buildings were massive, they had quite minimal façade lighting. We wanted to light the top band, and all of the lighting was designed at prefix angles, so it only caught certain bits of the metal in a certain way, and reduced all of the upward spill of light.

“These little details all came together to make sure that, although we’re keeping to the dark sky requirements and trying to reduce the light pollution, we’re also not losing all of the vertical illumination.”

Smith continues: “We worked really closely with the planners to minimise any spill light from upward light. Where we’ve got lights around the perimeter of the building that are uplighting the façade, they are all angled, even at pedestrian level, so that there’s nothing going straight up into the sky. There are also a lot of capping details around the building that limit upward light spill. We also worked with the lighting manufacturers to get the right optical control, and making sure when we were lighting the roads, there was nothing spilling back onto pavements – we had quite a harsh cutoff with zero back spill. Everybody across the board thought about these things, whether directly or indirectly.”

This joined up thinking is just one of the ways in which Foundry feel that they worked well with Midgard, and the wider design team.

Cozens explains the collaborative nature of the project further: “The best projects are those where everyone accepts each other’s skillset and their expertise. It’s not to say that there weren’t disagreements, especially when it came to costs, but when we put the case forward for the cost, explain it, and educate the client, they were understanding.

“A lot of people in construction now have an understanding of lighting that maybe they didn’t have ten years ago – they understand lux levels and uniformity, but they also acknowledge that there is a little bit more that goes into it. Yes, we can tick a ‘light level’ box, but is it going to be pleasant? Is this lighting creating a sense of security and safety? These are the moments where our experience comes in and we have to educate the client. In this instance, they were very open to it; sometimes it’s a challenge, but here it was a lot easier.

“We were really involved in every intimate detail, for our sins in some ways, but it meant that the design that we had agreed on day one, we were able to deliver and maintain across the board, which is really hard to do in this day and age. It was challenging, but it was definitely something that, in the end, resulted in a better outcome.”

That’s not to say that this project wasn’t without its challenges. The biggest of which, according to Smith, was bringing it all to life in the middle of the pandemic. With work starting in the summer of 2020, the knock-on effects of prolonged lead times – sometimes taking up to six months for fixtures to be delivered – meant that, while some parties were keen to keep the project on target, the pandemic led to frustrating delays.

“The biggest challenge was managing these delays, because everybody was wanting to get the job moving, get installation teams moving, and silly things like missing components, missing drivers that were integral to light fittings, was holding up the process and preventing things from getting delivered.”

Cozens added that maintaining the integrity of the specification also proved to be one of the bigger hurdles to overcome. She says: “The contractor was always looking for the cheapest, quicker solution, so trying to keep them happy while also maintaining the design and not sacrificing too many elements was one of the hardest challenges.

“Trying to keep the project cohesive was also difficult. There are so many different spaces, from the large landscape, to the street lighting – so we had to balance all of that and make it feel all part of one unified scheme, especially when it was all done at different times and in different phases. The podium was finished a lot sooner than the masterplan; the street lighting went in first; the buildings were done separately to everything; it was all very staggered. So, trying to continue to keep that thread and link through the space, and keep the lighting consistent and enjoyable and still quite special was a challenge, but I think it has been done quite successfully.”

An integral factor to the consistent feeling across the site was in the illumination of the two residential buildings. Foundry was responsible for illuminating the interior amenity spaces, as well as the façades. This meant that, as Smith explains, there had to be a synergy between the interior and exterior lighting. “The buildings are heavily glazed around the amenity spaces, so there are a lot of connections between the interior and exterior. So, there was a conscious decision to make sure that there would be a continuity and balance between the inside and out, focusing on transition, making sure we had a consistency in colour temperature – we had tunable white inside and outside, so we could balance everything up. With this, there was definitely a considered, joined-up thinking process in how we transition from inside to out.”

Following the completion of Phase 1 of the project – with talks underway for Phase 2 – Smith and Cozens reflect on the lighting scheme with a lot of pride, particularly in the way that the lighting contributes to the overall aesthetic of the space.

“It’s a very calming experience,” says Smith. “Even though a lot of the light is focusing on surface materials, highlighting or leaving in darkness certain elements, the lighting feels natural. You seamlessly transition through the space without really thinking too much about it.

“The last time I was there, someone was sat out on the podium at six o’clock at night, on a chair, lying back with his feet up, and he looked like he was asleep, just enjoying the space in complete bliss. This just shows how, from a resident point of view, it’s being used and enjoyed.”

“It just feels at home – you want to go and explore, especially on the podium with all the planting, you want to see what is around the corner. That’s the bit that lighting does. You don’t necessarily notice, but that’s why you feel like that,” adds Cozens.

The project was recognised at the 2024 [d]arc awards, collecting not only the Spaces award for landscape lighting, but also the Best of the Best award – the highest accolade in the awards programme. A testament to the importance of crafting beautiful, well lit green spaces in which to escape the hubbub of of London city centre.

www.foundry.london

Tupac Martir

Fresh off star turns at IALD Enlighten Americas and Disruptia Madrid, artist and design extraordinnaire Tupac Martir has become a must-see presence in the lighting world. arc sits down with Martir to learn more about his interest in light, and his vastly diverse areas of expertise.

Every once in a while, you come across a designer that stops you in your tracks. Someone with a portfolio of work so awe-inspiring, eclectic and diverse, with the kind of character to match, that you just have to drop everything that you are doing and get to know them.

One such designer is Tupac Martir – founder and Creative Director of Satore Studio. After a standout presentation at IALD Enlighten Europe in 2024, followed by a keynote session at IALD Enlighten Americas in San Diego, and more recently taking part in the latest Disruptia event, led by Light Collective, in Madrid, Martir is a must-see on any talks programme, thanks to his unique approach to art, technology, and design.

Based in Lisbon, with a satellite office in the UK, Martir’s work with Satore Studio spans live performances, fashion shows, art installations, and architectural lighting, with his multidisciplinary studio always looking at new ways to combine design and technology to bring bold, beautiful concepts to life and deliver dazzling, memorable virtual experiences to audiences worldwide. Across the full scope of his work though, Martir has always sought to push the boundaries of what is possible.

In an exclusive interview with arc, he says: “I always have this joke – if it is a challenge, if it’s difficult and you say, ‘how are we going to pull this off?’, I’m your guy.

“There was a time where I was never the first designer to get called in. I was always the second designer, called in a moment of panic. I remember talking to my mum, and she asked me ‘how come every time I talk to you, you are doing a job that is last minute and panicked?’ I said, ‘because that is when they call me’. She said, ‘well, why don’t they call you from the beginning?’ I don’t know, mum.

“But I think I made a reputation of exactly that; if it’s weird, if it’s quirky, if it has a lot of challenges, then I get those jobs. But the challenge is the part that I enjoy.”

Challenging himself is something that has been true of Martir even dating back to his studies. A student at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, his initial interest was in Photography and Psychology, but true to his multi-disciplinary approach, this very quickly expanded.

“Photography was going to be my minor, and psychology my major; within a semester, I realised that I had it wrong, and I wanted to make photography my main thing,” he recalls.

“When I arrived at college in my first semester, one of the reasons why I went there was to study under Father Don Doll, who is a photographer for National Geographic. In my first semester, I couldn’t take his class, as I was just a freshman, but then he gave me a pass.

“That is when I realised that actually what I want to do is art. So, immediately, I had to go back and do the basic courses of art. And people usually take art courses as their electives, but because I was doing art, my electives became Calc Three, and Physics, while I was going through the basics of art – drawing, life drawing, painting, sculpture. Here, I ran into a beautiful man by the name of John Thein, who took me under his wing and became my mentor. Through him, I discovered painting, and suddenly the world just opens up. I would say that this is where the journey of my multidiscipline-ness comes from.

“Even though I went to a really small school that is not known for the arts, I was very privileged, because I had John, who saw me and thought, ‘I’m going to make an artist out of you’. Because of that passion that he had for me, it made all the other professors more aware of what I was trying to do.

“In my last year of school, my two main professors would come in and critique my work every two weeks, but they would always invite somebody else from the faculty in – sometimes it would be an art historian, or someone working in digital art. I went to a Jesuit school, and I had a brilliant professor who taught me God in Humans; as a Jesuit telling me ‘As a man of faith, I believe in this book, but as a man who understands the world is everything, I believe in science’, that element of it opened up really interesting conversations around the work that I was doing.

“And so, that has always cemented the foundations of what I do as an artist, and what we do as a studio. If we jump forward to where I am right now and all the work that I’m doing in so many different, varied elements, it’s because of that. It’s because I can see how the work that we’re doing, and the knowledge that we’re gathering in the studio, can be repurposed in so many different places, and how the knowledge that other people have can be brought back into some of the things that we’re doing.”

After graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting, Drawing, Etching, Photography and Digital Art (with a minor in Religion and Philosophy, no less), Martir “jumped around” a few different places, before starting work at the Opera House in Mexico City, initially assisting another artist who specialised in working with paper but, as has been the case throughout his career, this soon expanded to a lot more.

“I did what I still call the weirdest Master’s in Theatre Design for Opera, because I never took a class, but I used to assist everybody, from the costume department, the wigs department, the makeup artist, the lighting designer, the video designer, the sound designer; at one point I assisted a conductor, I assisted a singer, a dancer – I worked across the entire element of what they did.

“Alongside this, I started doing events and parties in Mexico City – every week, we were hosting different parties, so I’m learning more about lighting, about video, about how you make spaces, and how you think in a truly three-dimensional way, where also time and space are really important.”

Across his varied working career to this point, light had always been present, without necessarily taking centre stage. It wasn’t until he started working for MTV LATAM – eventually becoming Art Director at the tender age of 27 – that he started to really learn more and appreciate the power of light.

“At MTV LATAM, I was putting together something like 45 hours of content every single week, and having to learn how to use cameras, and how things were going to look on camera. One of the things that came from that was, at the time I was thinking more in terms of set design and prop design – I remembered making things that looked really cool, but when they were badly lit, they looked horrible. I remember seeing things done in which I didn’t do a great job, but the light was making it better. So, I said to myself, ‘I need to learn about light’. Because I was at MTV, I met a bunch of bands, and by meeting bands, I met their lighting designers, and their audio designers, and became embedded in that world.

“I said to a friend of mine one day that I really wanted to learn more about this, and he told me to go to the back of the stage, and speak to the guys working there, learn how to hang a lamp, how to put it together, learn the electronics of it all, do the training of a normal technician. He then said to me, ‘You think in three dimensionality in a way that none of us do. So, the moment that you understand how all that gets put together, your brain is going to be able to analyse how to programme and how to do all of these things’.”

With this additional knowledge now in place, Martir moved to the UK in 2009 to enrol at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama to study for his Master’s in theatre design. If things weren’t already going well for Martir, this is where his career truly took off, as his thesis project, Nierka, ended up being his first official show.

“The idea for Nierka was ‘I’m going to tell all of you where this is going. Screw just doing things in one way. We’re going to have opera singers, a children’s choir, an orchestra, two DJs, a five-piece rock band, and we’re going to have 15 dancers, and there’s going to be things moving, and there’s a combination of ballet and movement and painting and technology. And that almost sets up everything that I do. To the point that I always say the basis of what Satore Studio is, is based on the things that we did in Nierka.”

To that end, Martir explains that, since the official formation of Satore, he has always tried to foster a welcoming and collaborative spirit.

“I never meant to have a studio. But because I was starting to get booked so much, I wasn’t doing jobs anymore, I was designing them, and then sending freelancers to do it. So, my accountant said to me ‘you need to become incorporated, and you need to open a company’. It occurred very naturally, and it was very weird. God knows, HMRC hated my butt for two years, and they were correct to hate me, because I was out of my mind, I had no idea what I was doing.

“This is where Nierka and Satore are so tied together, because the ethos of the studio comes from a place of exploration; it’s a space in which all the arts are welcome, in which science and technology are welcome. It all comes from what I would call the humanity that exists in the studio.”

A prime example of this humanity is the presence of a fridge in each studio. But, unlike the fridge that might exist in any other office, this is not a place for staff to store their own lunch. Instead, it is always full of food that the team orders in, so that staff always have whatever they need.

“Your wage is your wage; you should not be using your wage to pay for your lunch while you are here. I take care of you, because I know that you are taking care of me,” Martir explains. “And so, this makes us have lunch together every day, and it generates a completely different type of camaraderie that wouldn’t exist otherwise, where you can sit down with colleagues who are working on different projects, and find out more about each other.

“I never say that we are a family, because families are dysfunctional as hell, let’s be honest. It’s more like-minded people coming together, like being in a social club.

“You are always going to have options of where you want to go and work, where you’re going to spend your time, the people that you’re going to spend your time with. You can sometimes hit the triple jackpot and get paid very well, do amazing work, and have a lot of fun doing it. The reality is sometimes you have to pick one or two of these, but I always thought that at least the place should be fun.”

This approach also extends to Martir’s “mission statement” for the studio as well. Elaborating, he adds: “It has to be a place of creativity, a place of openness. It has to be a place where technology is acknowledged as a collaborator. Nothing is permanent, and at the end of it all, it’s always about the humanity of things. There’s always been a joke that I put humanity into technology, because I see it as a collaborator, but for me, those are the most important elements. And I hope that if you were to speak with people that passed through the studio, they would tell you what a good place it was to work and how big of a school it became.

“I had an entire conversation at one point with the guys at Epic in the middle of the pandemic, when my team was being stolen left, right, and centre, and I was like, ‘Guys, this is not fun’. They said ‘Yeah, it’s not fun for you, but it’s great for us, you make really good people’. Although it stings, you also take it as a source of pride, knowing that you’re preparing people to do good things and to think in a completely different way to what they’re used to.”

As a practice, Satore Studio has built an impressive, diverse body of work, including fashion collaborations with the likes of Alexander McQueen, Vivien Westwood and Prada, live music performances – including Beyoncé’s headline performance at Glastonbury Festival – and one-off art installations. Across all of this work, light plays an integral role, not only in enhancing the visual aspect, but in stirring up emotional responses in the viewer.

Martir adds: “What I enjoy most about light is how ephemeral it is. As an artist, you always try to find that conversation in which I am going to propose something, and I need you as an audience member to allow me to tap into your bag of emotions, and your bag of memories, so that we end up complementing the piece, and I think light is one of the true mediums in which that happens.

“I can put a blue light at 35% on a tungsten source being shuttered in a certain way, and it’s going to create an emotion in you. I am making the emotion, but you create the emotion for yourself, and you draw it from your own experiences. So suddenly, everything is a collaboration between me and the audience.

“The reason why I love painting is because I make a single frame, and that’s it. The idea of lighting is almost like painting in motion, painting through time, which is beautiful. When you imagine some of those spaces in which the light comes in – the grandiosity of it or the hiddenness of it – it generates places where you want to go and see, and when it works with things like music, it can generate emotions in people that they had no clue about.”

Alongside his work in fashion, entertainment and the arts, Martir explains that Satore Studio does also work on more “traditional” architectural lighting projects. Although these still typically have a more artistic flair to them.

An example of this, Martir tells, was through a collaboration with Gucci. “We did a party for Gucci in a house near Piccadilly, and there was very little power. We weren’t able to bring a generator, and I needed to give a sense to each of the rooms, so I ended up changing all of the light sources throughout the house, buying 15W light bulbs, and then sitting downstairs with my paint and hand painting every single one of the lamps, so every room would have a different feel, based on me painting the lamps. It was very artisan.

“When I work in architectural lighting, I come in and I change things that are there – usually coming in at stage one so that my work gets embedded with the architecture from the beginning. It’s funny though, because basically, I’m allowed in at stage one, I lead stage one from my side, stage two is when everybody else gets introduced, and then halfway through stage three, I’m not even allowed in the door. My nature is to keep changing things – the more things evolve, the more I want to do, and one of the things that I learned in architectural lighting is that once you’ve done your work in stages one and two, when we get into stage three, unless something major happens regarding the design intent, you’re not touching the design anymore. Congratulations, you’ll see it in five years.”

However, while Martir says that his nature is to change things as projects evolve, when reflecting on his overall approach to projects, he says that the main thrust of his ideas comes very quickly.

“Most of the time, I’ll get a brief, and the first thing that I want to do is talk to somebody, before I even start imaging what I want to do; I’ll talk to the director or the fashion designer or the production company. I need to have that crowning element right away, so that I understand my boundaries, and understand what elements I have in my toolbox, and what the things are that I need to worry about, my restrictions – usually these are things like power, budget, height – and then from there I start working around it.

“The reality of it is I’ll probably have 90% of my design done in the first five minutes. The main element is done really quickly, because I can understand what I need, and then I’ll go into the boutique elements and refine everything according to what we’re trying to do, especially with light.”

This immediacy is something that Martir puts down to his varied background, and in particular his ‘Jack of all Trades’ time at the Opera House in Mexico City. “All the work that I’ve done in 3D worlds, whether it was sculpture, set design, all these elements have given me the opportunity to understand. A lot of it comes from having done every single job at the Opera House to understand what elements will make something good.

“I don’t like to say I take risks – a risk is a father or a mother who has to run through a bomb or a warzone to try and get food for their children. Me making a decision of red or blue is not a risk, it’s an educated decision. But I feel very comfortable with the tools that I have at my disposal. I study a lot, I read a lot, my brain is stimulated on a regular basis about the possibilities of what can be done.”

Reflecting on such possibilities, Martir cites his collaborations with Alexander McQueen and Vivian Westwood as particular highlights – “these are icons that go beyond fashion, and have transformed the landscape of culture and arts”. His collaboration with McQueen was for Plato’s Atlantis, which would become the fashion designer’s final show.

Meanwhile, he talks of his work with Prada, Carsten Holler and Nick Reynolds as standouts for the way in which they worked together. “We were trying to transcend how architecture can be achieved, and how it can be seen.”

A particular standout though, is Háita – a project that served as a foundation for Martir’s presence in Lisbon. As a project, Háita was born from the exercise of imagining how a dancer’s choreography could be explored inside out. Combining dance with music and state-of-the-art technology, the installation took the form of a quadripathic exhibition of four projections of the same choreographed piece. The dance was a mixture of styles, incorporating ballet, Portuguese vira and Mexican traditions – captured on film, but also through volumetric and motion capture technology. The installation was activated by a dancer, illuminated through a projection based on an electroencephalogram made of her brain, and representing the patterns of her brainwaves throughout the choreography, building an inverted image of how a dancer imagines her own choreography.

“As a project, this transcends the simple, and looks to find a meaning that goes beyond entertaining somebody,” Matir says.

As for dream collaborators going forward, Martir says that, aside from lighting La Sagrada Familia, or working with Pearl Jam, he doesn’t have many dream clients, but rather, he is more interested in continuing to push the boundaries of what is possible.

“There are people that I would love to work with, but at the same time, I think that the part that I am more interested in is the challenge, and how we make something new. How do we reinvent something? How do we turn around the scales of things and make people have a new vision of what can be possible?”

Central to this mindset, Martir is always trying to keep abreast of the latest developments in technology. Having been in the know about AI and VR since the mid 2010s (“I’m part of the OGs of the second wave of VR”), he is always looking at courses and forums to keep up to date with new developments. However, he is keen to ensure that the work itself takes centre stage, not the technology used.

“I don’t care about what the technology can do, more about whether I can bend the technology to do what I want it to do. That for me is always more interesting,” he says. “How can I create new forms of entertainment, new forms of storytelling? Technology is a character; the way that the graphics card that you use and the software that you have is like building a character in the same way that an actor needs to realise what their backstory is and how they behave and move, it’s the same thing. It’s just that technology should never be the main actor of your story – it should be a supporting actor who gets a scene.”

Similar to the way he keeps an eye on future developments in technology, Martir and Satore Studio are also firmly keeping their fingers on the pulse of emerging talent in the design world too. Keen to nurture and mentor the next generation, Martir has established the Satore Academy – an initiative based on his desire to give something back.

“Not everybody can come in and be an intern, and sometimes people just need somebody to talk to that has a bit of knowledge,” he said. “We end up taking between six and eight people on every time we do it. We’ve had people that are starting their Master’s, have just graduated, are in the middle of school, and we help them out in any possible way, giving them direction or even sometimes just having a bit of a therapy session. We want to act as a sounding board for people who are looking for something a bit different, or are a little bit lost and want to change career or pivot, and give an opportunity to people in a different way. It is something that we feel very, very proud of.”

Finally, as a man who is always looking to the future, what are some of his bold predictions for the design world in the coming years?

“The more things that we’re doing in real time, that we’re doing with parametric design, some of the things that are happening with technology, at some point reality is going to hit, and all of the AI-generated visuals that people are making are not going to be the right thing,” he said. “But I think that there’s a lot of things that the industry can do better in terms of making us understand the true possibilities of the products, and also the way that we are understanding what humans can see and how we’re seeing the world. We’re going to start finding new, subtle ways to do it.

“I think we’re just scratching the surface of what we’re going to be. With things like mixed reality, once we get this working properly, welcome to the fourth dimension. Suddenly there’s going to be an entire new world to explore, and I think that is going to be a very interesting space.”

So, as we venture forth into this brave new world, I can think of few designers more suited to lead us into the future than Tupac Martir.

Anolis appoint Eloise Reed as International Specification Manager

(UK) – Architectural LED lighting brand Anolis, part of A Robe Business, has appointed Eloise Reed as its International Specification Manager.

Based in the UK, Reed will represent the Czech-based manufacturer across international and domestic markets, which will include streamlining the design support and tender processes for clients, and boosting the Anolis profile within the architectural lighting community.

Reed brings a broad and diverse background in lighting design and specification, having worked across live performance, museums, architecture, and high-end visual environments. Her new role will also involve fostering connections between Anolis and the wider Robe Group, strengthening brand cohesion across the group’s premium lighting solutions.

Reed’s career began in Australia where she studied at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) and gained hands-on experience lighting events in non-traditional venues. Her early work included lighting design for raves and warehouse parties, alongside technical roles at rental houses and theatres in Melbourne.

Reed’s background work with complex lighting control systems, museums and galleries aligns with Anolis' emphasis on bespoke and sustainable lighting solutions for built environments, urban and other public spaces, and is described as a great asset to the Anolis team.

Reed comments: “There is a lot of interesting work to be done and a great team of people in place to whom I look forward to collaborating with as we take the brand to the next level.”

She feels this is “a highly opportune time” to be part of the Anolis journey, as the true potential of its current and developing LED lighting products plus the synergy and crossover between the Robe Group’s other brands starts to play out.

Introducing the Business of Design

https://vimeo.com/showcase/11485671/video/1034342353

Speakers Anna Sbokou, Founder, ASlight, talks about the business of light existing to engage, educate, and elevate the next generation of lighting leaders. With a board comprised of luminaries from all aspects of our lighting industry, the Business of Light works to empower individuals through education and mentorship to grow and sustain lighting businesses. Come and learn about the kinds of programming BOL offers, and how you can leverage the knowledge to accelerate your business.

Signify names As Tempelman as Chief Executive Officer

(Netherlands) – As of September, As Tempelman will become the new Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Signify. Subject to his appointment to the Board of Management, with Željko Kosanović continuing as interim CEO until then.

Gerard van de Aast, Chair of the Supervisory Board of Signify, comments: “We are thrilled to appoint As Tempelman as CEO of Signify. His strategic vision, energy and proven track record in driving sustainable growth, while building an inclusive high-performance culture, made him the clear choice to lead the company forward.”

“With more than 130 years of history, Signify has always been a pioneer. The innovation, passion, and purpose that define this company are incredible, and that’s what drew me here. I am very excited to be joining the team,” says Tempelman. “Looking to the future, I believe there is a real opportunity to grow. To build on existing strengths, unlock new possibilities, and continue to lead the way in lighting and beyond, improving lives for people and communities around the world.”

As Tempelman currently serves as CEO of sustainable energy company Eneco, where Tempelman has delivered against ambitious business and climate initiatives, tripling company profitability since 2020, while reducing GHG emissions by 40% per annum. Before Eneco, As held senior leadership positions at Shell in Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

An Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) will be held in July, at which shareholders can vote on As’ appointment to the Board of Management.

Available Light announces leadership transition

(USA) – American lighting design firm Available Light has taken a significant step in its long-term succession planning with an expanded executive leadership structure alongside founder and CEO Steven Rosen.

The newly formed team of Executive Directors will oversee key areas of the company’s operations. Matt Zelkowitz will lead the Built Environment division, Bill Kadra will head the Trade Show division, and Annette LeCompte will oversee Operations. The leadership team is supported by a Board of Directors that includes Derek Barnwell, Kate Furst, Rachel Gibney, and Ted Mather.

“It’s incredibly gratifying to experience the evolution of our firm over the past 33 years, growing from a single employee to a team of 35, with studios in six cities,” said Rosen. “This success is a testament not only to our extraordinarily talented and accomplished team, but also to our clients who have long understood the power of experiential lighting. The work we do at Available Light is integral to enhancing the stories our clients want to tell.”

“As we contemplate our future and prepare for Rosen’s transition over the next few years, we’ve worked diligently to ensure Available Light has the depth and sustainability to thrive,” said Matt Zelkowitz, Executive Director–Built Environment. “We've cultivated generations of designers, ensuring a solid long-term outlook for the firm.”